Like applying to other jobs, since I don't actually know if this one will work out. Or continuing to study up on computer science stuff.

I'm giving myself a little bit of time to goof around (and hopefully hear about that position), and then I'll buckle down and get back to it.

But all that job hunting stuff brings up some things I guess I need to get out of my system before moving on to my current series.

Job hunting is rough, not just for the uncertainty, not just for the worry, but because you get rejection after rejection. (Got rejected for another position just the other day, which is frustrating to no end).

And it brings back a feeling I've had, off and on over the years, in one situation or another. That deep-seated frustration and misery that comes from feeling like you could be amazing, if you just had the chance. If someone would just believe in me enough to hire me. Or give me the training and experience I need.

I know the world doesn't owe me anything. I know that I can't really blame them for not seeing what feels like a glowing sun inside of me (or perhaps I should use Camus, and call it an "invincible summer", though some days it doesn't feel quite so invincible).

But it's just so very, very, frustrating... to not be able to bring it into being. I hate sounded whiny, or self-pitying, so I try not to complain about it too much. "It is what it is", and I hate that saying. It's not the army's fault, for example, that they need to fill various positions and saw me as an appropriate person to use in one of them. Even though I had wanted to go into Human Intelligence, even though I'd taken the Defense Strategic Debriefer Course (which I enjoyed, but never used professionally, so from the army perspective ought to be considered a waste. I mean, the whole bit about building rapport and whatnot is kind of useful in interviews and other places, tbh, and I think I do okay at it in person. Have trouble branching off from that into other things, i.e. people generally need to feel like you're in touch with them and have an ongoing relationship to really network right. Sending articles you know they'd be interested in, or newsletters like my aunt used to do... and I'm really awful at that sort of thing. So I appear to do well enough initially, but not to the point where someone I met as a one-off will open doors six months down the road when I need a job. And my friends and co-workers seem to like me well enough to send some openings my way, but that's apparently not enough to get whoever is hiring to take my application seriously. Maybe it's my resume, though I've had people review it often enough that I think that shouldn't be the issue. Other than currently trying to do a career change, and thus not having a lot of work experience in the field. Enough of that, though.)

Anyways. I was doing my darndest to try to say "this person should be developed in this way", but nobody cared.

Which is ultimately why I left the Army. I don't blame them, they're a large organization and they've got positions to fill. But...

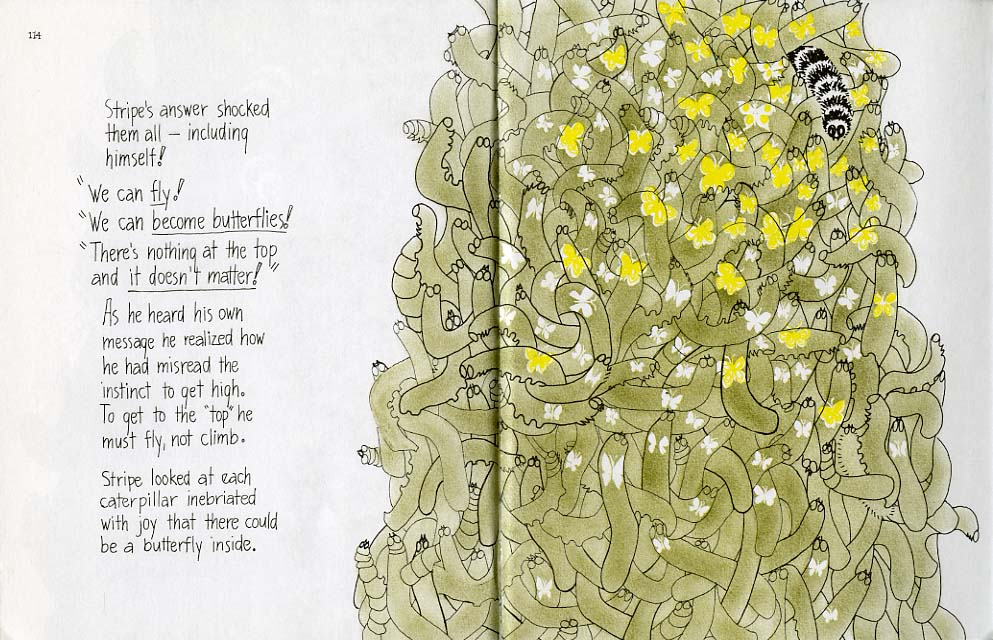

Yet again I find the best analogy in Hope for the Flowers. We're all caterpillars, with the potential to become butterflies. But becoming a butterfly isn't as easy as following some predetermined path. It's as much about following your instincts, with no real certainty about what's going to happen next, as anything else. I want to be a butterfly, have some sort of instinct (that I can't explain) about what sorts of positions are necessary to make that happen...

And I just can't seem to make them occur.

And - the reason I'm posting this, really - that sense of frustration is the driving force behind a lot of my current posts.

Because I don't think I'm the only one who feels that. I'm actually pretty sure most people do, other than the lucky few. Like this scene from the book:

Where the caterpillar realizes everyone he sees has a potential butterfly inside.

But (as my own experience, and frustration, shows), reaching that potential is not easy. You have to create the right environment for it to happen. You have to have the resources to do so.

So it is easier for some than for others. My Little would probably not be able to do softball and basketball if I wasn't a part of her life. She'd have probably missed far too many practices while her mom was at work. And in middle school she'd probably have had a horrible grade in band, since she'd probably have missed some of her concerts.

Which may or may not have been a problem. She doesn't have an interest in playing professionally, so not playing would not have prevented her from transforming into her own personal butterfly... but it could for someone else. And schools often look at how many extracurriculars you do, so not being able to reliably get to practice could affect what school she gets into (though she might have found another way. One never can tell.)

None of which is probably too big a deal, because she's expressed an interest in running a daycare, so she's not likely to need an Ivy League education. Helping her turn into her particular butterfly is more about helping her keep her grades up, guiding her a bit on some classes to take (she took a child care development one earlier this year, and a business one), and so on and so forth. If I had the resources, when she got older I could probably talk to her about giving or loaning some start up capital, but if she's serious about this I'd probably direct her towards business plans and small business loans, assuming other things occur in the next few years. (She may lose interest, or other things may happen, and she probably ought to actually work in a daycare for a bit before trying to start her own business... and maybe she'll decide she doesn't care about running it herself. Who knows?

Her potential butterfly is different than mine, her talents and interests are different, so what she needs is definitely not what I need.

If I were to try to imagine a true utopia, I think that would pretty much be it - that everyone was able to reach their full potential, and turn into beautiful butterflies. And (if you believe in God, and trust that He knows what He's doing, which can be quite a lot to ask) I suspect that everyone's butterfly is pretty darn amazing, and would lead to a pretty awesome society.

I don't really have to understand why people are drawn to one thing or another. One of my brothers is a teacher, particularly for special needs kids. He originally went to college for something else, but took a business calculus he really enjoyed, wound up helping some of his classmates with the material, and realized he liked doing that sort of thing. He's really good at breaking things down into basic steps and explaining them (which he also does when teaching someone a new boardgame. I do sometimes feel he goes a little bit slow for my taste, but then I'm not generally his target audience.)

People feel called to do all sorts of different things, from teaching to nursing to national security. Sometimes they get paid to do it professionally, sometimes it's a side job or hobby, and they just hold down a job to help pay for that hobby.

The fact that so many people out there feel the sort of frustration I do, feel an inability to become who they want to be, feel stymied by a world that just doesn't care...

That bothers me to no end.

I don't believe in compulsion, for the most part. I think the government is all too often a sledgehammer used to crack a nut.

But I also know that people turn to it when other options fail. That the sentiment "there oughta be a law" comes when something isn't being taken care of privately.

If the nut needs to be cracked and all you have is a sledgehammer, than sometimes that's what you do.

When the top 1% have more money than the bottom 90%, when the minimum wage in 1956 was $1.00/hr, and a CPI inflation calculator shows that's equivalent to $9.49 today, and today's minimum wage in Illinois is $8.25/hr...

And that's just one example of how wages haven't kept up with inflation, how the top 1% sucked up more of the money and the bottom have less and less to live off of...

When there's so much out there discussing this that I feel you either get it or you don't (and if you don't, you probably have a strong self-interest in NOT getting it, and are almost willfully choosing to dismiss it all)...

I have to wonder how anyone in the top 1% can look at themselves in the mirror and feel proud of who they are.

If life is a race (which is not a given), then they're winning it... but they're winning it when over half the competition is tied down with a ball and chain.

But whatever. There's enough resentment of the 1% that I don't feel I'm contributing much of anything by discussing it. I sometimes like to imagine I have an audience from that stratum, but I also imagine they'd fail to be persuaded by any argument that sounded like sour grapes.

I do find myself wondering, though, whether they're truly any happier with our current system then those of us 'have-nots'. Whether, with all the resources at their disposal, they're using them to become the butterflies they're called to be.

An odd question, I suppose. I don't have any personal experience with anyone at that level, after all, and the wealthy can get away with stuff the rest of us don't (since "the poor are crazy, the rich just eccentric"). Many of them, from what I can tell, actively support some great causes.

But... some of them also appear, perhaps, even more constrained by social norms than the rest of us. Even more worried about other people's opinions, and making a good impression, to the point where they're unable to be their authentic selves (and clearly unable to become their butterfly).

And although I can't judge any one particular individual, we all know that the class as a whole has the resources to make serious changes if they wished. (I'm not advocating a particular way of doing so right now... I'd actually prefer private philanthropy over government regulation, tbh, but there's apparently not enough voluntary private effort to get the job done, so once again... if you've got a nut to crack and all you've got is a sledgehammer, that just might wind up being what you use. The 'job', by the way, is catch-all for all the various inequalities going on right now.)

The fact that they don't shows a certain complicity in and acceptance of a status quo that leaves far too many people miserable.

Anyways. To bring this back full circle - I'm currently quite frustrated, and tired of knowing that the world just doesn't care, and wish we could all do our bit to make a world where everyone (not just me) could live up to their full potential.